Becoming a cosmopolitan globalist.

Hello, all! This week I have an exciting new partnership to announce. I'm teaming up with Claire Berlinski, who has a newsletter called The Cosmopolitan Globalist that is not unlike this one.

The Cosmopolitan Globalist was borne of the observation that genuinely global news coverage has all but disappeared from the Anglophone media. It's a collaboration of almost 70 writers, journalists, academics, politicians, and analysts – shepherded into a single platform by Claire in Paris and Vivek Kelkar in Mumbai – who bring you reporting and analysis from around the globe. And now I am one of them.

From now on, I will be sharing some of The Cosmopolitan Globalist's work here and vice versa. You can subscribe to that newsletter here.

You can pitch me ideas for who or what to feature in this newsletter or send story tips: c.maza@protonmail.com or cmaza@nationaljournal.com

This week I'm featuring Monique Camarra's essay What does "an election" mean in Russia? Monique also co-hosts a new podcast called the Kremlin File that I highly recommend.

What does "an election" mean in Russia?

The past week saw fresh criminal charges levied against imprisoned Russian dissident Alexei Navalny and his top aides. They stand accused of running an “extremist group.” According to Russia’s Investigations Committee, which deals with major crimes in Russia, Navalny and his top allies created their Anti-Corruption Foundation, or FBK for short, “to carry out extremist activity aimed at changing the bases of the constitutional structure of the Russian Federation, undermining the public security and state sovereignty of the Russian Federation.”

A curious charge. Simultaneously, Russia’s Justice Ministry added an array of people and media organizations to its list of “foreign agents,” including MediaZona and OVD-Info. Both outlets are critical of Russian authorities. OVD-Info documents politically-motivated arrests and violent assaults. The ministry designated MediaZona’s editor-in-chief, Sergei Smirnov, a foreign agent. Also a curious charge.

To understand these claims, we must understand the system Putin has erected to ensure there will never be a free and fair election in Russia—at least, not as citizens of Western democracies understand those words. Indeed, when The Cosmopolitan Globalist asked me if I’d write an article about the recent Russian elections, I replied, “Elections? There were no elections. What’s important is the ritual they call an election—and what it really means.”

The systemic opposition

Although termed “legislative elections,” the events that took place between September 17 and 19 should not be understood as a political contest in the Western sense, that is, one in which the outcome was genuinely uncertain. It is more useful to view the ritual as a table set for the Kremlingarchs. The term “Kremlingarch” is owed to Ilya Zaslavskiy, a researcher who studies Russia’s post-Soviet kleptocracy; he argues against the word “oligarch,” which might confuse readers by suggesting the men in question have independent wealth, or run private businesses, in a system with aspects of a market economy and an independent judiciary. Since this is not at all how Putin’s Russia works, Zaslavskiy invented the word “Kremlingarch.” He is right to say it better evokes the status of the wealth handlers orbiting the Kremlin among whom state favors are allocated.

Whatever we call them, the elections were designed to reinforce their position, and they were anything but free and fair. The conditions for such a contest simply didn’t exist. Last summer, when I interviewed Masha Gessen, author of The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia, I naively asked whether Russia’s opposition parties might have a chance in the upcoming Duma elections. Masha rebuked me, telling me it was a Western conceit to speak of the Russian opposition. Yes, Russian voters have a menu of parties from which to choose. But they are all controlled by Putin and the Kremlingarchs.

This state of affairs was not achieved overnight. It was Vladimir Surkov, Putin’s former political technologist, who hatched the idea of the “systemic opposition.” It’s a neat scheme. Yuri Felshtinsky, who with Alexander Litvinenko wrote Blowing Up Russia—Litvinenko was subsequently poisoned with Polonium-210—explained the way it works to me. The Kremlin funds and controls both left- and right-wing parties. Russian Duma representatives don’t initiate legislation; they receive it from the Kremlin. Their job is to pass it and ask no questions. Russia’s democratically elected politicians, in other words, do anything but the job they were elected to do. Duma representatives warm their seats only to maintain a façade of democracy, providing a veneer of legitimacy before international bodies like the United Nations.

But Putin needs to control all of the parties in the Duma through any tool he and his cronies can devise because the Duma is there to protect his people, not the Russian people. How else could he ensure, for example, the passage of a law classifying the personal data of anyone under state protection—such as the one the Duma quietly passed in 2017?

Russian citizens are hardly blind to the problems plaguing the Russian state. They are well aware of Russia’s prolonged economic stagnation, the inflation, the mismanagement of the Covid pandemic, and a series of environmental disasters. This is why Navalny’s anti-corruption message was well-received—and why Russians have taken to calling United Russia the Party of Crooks and Thieves. God forbid they be allowed to vote for the candidates they really want. It is a risk Putin cannot afford to take.

Foreign agents

After payrolling the systemic opposition, Putin further ensures no true opposition figure can make it onto the ballot through his control of electoral commissions, and—here is where the charges against Navalny come in—through an increasingly severe law against so-called foreign agents.

Beginning in 2018, and accelerating in the runup to the recent elections, the Central Election Committee made a series of changes to the electoral law, giving Putin more power to filter out undesirable candidates. The Kremlin also tells election workers what to do, as we know, for example, from a recording leaked on September 3 to Novaya Gazeta. In the audio, Zhanna Prokopyeva, a municipal administration adviser, may be heard telling election workers to be “cold-blooded and calm.” She explains how to falsify election results to ensure the victory of a “certain party,” meaning United Russia. “We are interested in seeing a certain figure and a certain party—42 percent to 45 percent on the party-list voting,” she says.

Since 2012, and at a growing tempo since 2019, Russian authorities have systematically designated opposition figures “foreign agents,” a label reminiscent of the Soviet epithet, “enemy of the people.” Likewise, the Kremlin terms opposition civil society organizations and media outlets “extremist organisations.”

This serves a number of purposes. If you’re a foreign agent, you can’t run for office. Not only does the designation destroy a candidate’s reputation, it costs a fortune: Kremlin-controlled courts hand down steep fines—on average, US$4,000—per putative offense. Donors who might bankroll candidates are scared off by the prospect of coming under state scrutiny for donating to an “extremist group.” No one wants the hassle. If this message isn’t clear enough, there is of course prison and poisoning, both for the unauthorized candidates and their families. But it usually suffices to deem a candidate a foreign agent.

This doesn’t mean all opposition activity has come to a grinding halt. Sonya Grossman, for example, a journalist and activist who was placed on the list of foreign agents, now hosts a podcast describing the new and severe limitations on her life and career. It’s called “Hi, you’re a foreign agent.”

Navalny is the one Putin really fears. The lawyer and founder of the Anti-Corruption Foundation has repeatedly exposed the ways Putin and his Kremligarchs steal anything that’s not nailed down. Navalny had to close the FBK because it was deemed it an extremist organisation—besides, political activism is hard to carry out, if not impossible, from his cell in the Vladimir Oblast labor camp. Yes, he’s been able to send editorials to Western publications. Vladimir Milov, an FBK activist in exile, still runs a YouTube channel called Why Russia Fails. But this doesn’t have the impact of running campaigns in person.

This is why Vladimir Kara-Murza, another vocal opposition figure, insists upon campaigning in Russia and won’t countenance the idea of going abroad, even though he’s been poisoned twice. “A Russian politician has to be in Russia … after both poisonings, after I was physically able to, I would go back as soon as I was able to and I did. It’s a question of principle,” he says.

A candidate who manages to get on the ballot despite these obstacles becomes the object of even more creative Kremlin machinations. To confuse voters, for example, the Kremlin puts other candidates with the same name—and once, the same appearance—on the ballot. Boris Vishnevsky, for example, was an opposition candidate running in St. Petersburg. He was not the only one:

The Kremlin also goes to great lengths to blindfold anyone looking for polling irregularities. In the recent election, Russian authorities barred OSCE observers as a hygienic precaution against Covid19. The Russian electoral watchdog Golos was shut out, too, ensuring there were no independent election monitors save a bogus array of pro-Kremlin EU observers such as the French far-right deputies Hervé Juvin, Jean-Lin Lacapelle, and Thierry Mariani; the German far-right deputy Gunnar Beck; and Slovak independent deputy Miroslav Radačovský. (For their pains, the deputies were disciplined by the European Parliament, which accused them of taking luxury trips in exchange for positive reports and barred them from going on further election observation missions on its behalf.)1

What matters is who counts the vote

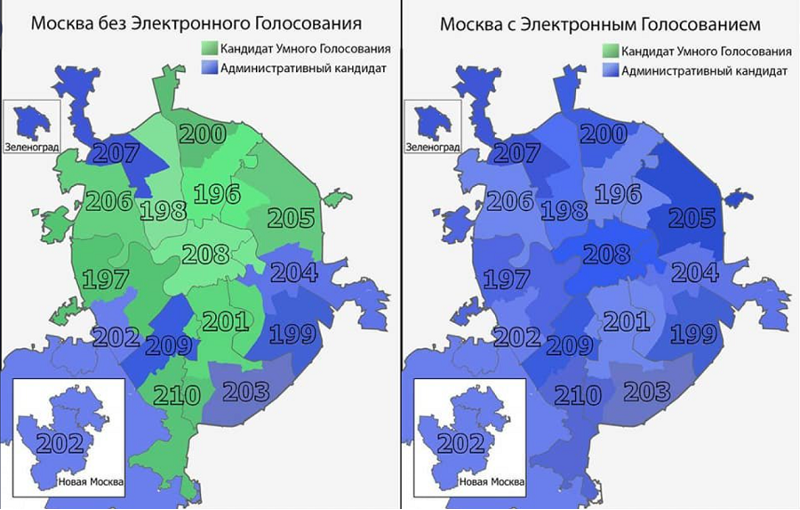

The force of authoritarian power was in full display during the three-day voting period in September. The results, interestingly, display two Russias: one expressed by the tally of paper ballots the other by electronic voting. The conflicting results tell us, as in the apocryphal quote from Stalin, that it doesn’t matter who casts the votes—what matters is who counts them.

The state’s electoral machinery and pro-Kremlin forces outdid themselves. From the crack of dawn, civil service workers formed long queues at polling stations throughout Russia’s big cities, even though citizens could vote over the whole three-day span. The theatrical display was meant to show voters that United Russia had firm support despite polling indicating it was hovering near 26 percent. Workers who hadn’t planned to vote electronically were intimidated or coerced by their employers to vote online for United Russia. Independent candidates were beaten and harassed at the polling stations when they pointed out irregularities. In St. Petersburg, the cloned Boris Vishnevsky, shown above, was beaten by unknown assailants for complaining about these voting procedures.

For foreign observers, the most shocking development—and one with sinister global ramifications—was the cooperation of major internet platforms with the fraud. At the request of a Moscow court acting on behalf of the Russian state internet regulator, Apple, Google, Telegram, and YouTube obediently removed Navalny’s smart-voting app, which was designed to help voters coordinate their votes for maximum impact. They also took down any content referring to it.

The app, devised by Navalny and his team, showed voters how to cast their ballot for the candidate with the most chance of winning against the Russia United candidate in their polling district. Doing so, Navalny explained, meant that in some districts, voters would have to hold their noses and vote for a candidate they disliked, all in the name of ousting United Russia. We’ll never know if the system might have worked because of the most consequential development in these elections: the inauguration of electronic voting.

According to the paper ballots, genuine opposition candidates won a number of districts in central Moscow. Andrey Pivovarov, the leader of Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s Open Russia party, managed to win his seat from prison. The paper ballot tally from Kara-Murza’s precinct in central Moscow showed the KPRF (Communist Party) winning 27 percent of the vote, while United Russia clocked in at 20 percent and Yabloko at 19 percent. These results were mirrored in the victory of Sergei Mitrokhin, the Yabloko candidate for the Moscow City Duma, who won his seat with 35 percent of the vote. But all of these victories were overturned when the results came in from the electronic votes.

In principle, electronic voting is a reasonable innovation. It’s used in many democratic countries, even in Europe. It’s convenient for citizens living abroad or in isolated communities, as well as disabled voters. It’s safer during a pandemic than voting in person, and it reduces the cost of holding national elections. Above all, it has the advantage of tabulating votes instantaneously.

But not in Russia. Somehow, the paper ballots were counted before the electronic ones. The electronic results remained uncounted eighteen hours after the polls closed. Even when they came in, no one had any idea how more than two million Moscow votes had been tabulated. There was no transparent explanation. Kara-Murza noted that the electronic and paper ballots, had “nothing to do with each other.”

The statistician Sergey Shpilkin drew up a preliminary analysis of early turnout results; he calculated that 50 percent of the votes for United Russia were falsified. As for the electronic results, he said, statistical analysis was pointless. The electronic votes were “an absolute evil—a black box that no one controls.”

It is a bleak picture, unrelieved save for a hope known to all serious observers of Russia: In this country, change can happen with lightning speed.

“I have a surprise for [Putin],” said Kara-Murza. “The incontrovertible truth is that in those countries where governments cannot be changed through the ballot box, they will, sooner or later, be changed on the streets.”

Monique Camarra, a language specialist at the University of Siena, is the co-host of the Kremlin File.

Upgrade to a premium subscription by Clicking Here.

What I'm writing:

• I wrote about how Central Asia gained new significance for Washington after Kabul’s fall and about the 145 U.S.-trained Afghan pilots currently stuck in Tajikistan.

• My colleague Brendan Bordelon and I wrote an article about how a Senate bill to counter Huawei by funding 5G in Central Eastern Europe got derailed in a debate over the new U.S. International Development Finance Corporation’s identity.

What I'm reading:

• An investigation into 2.94 terabytes of leaked data, named the Pandora Papers, revealed new information about tax havens and offshore accounts held by billionaires and prominent politicians. The project was led by journalists from The Guardian, BBC Panorama, Le Monde, and The Washington Post. It revealed secret financial information about Russian President Vladimir Putin, former British Prime Minister Tony Blaire, Jordan’s King Abdullah II, Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, Cypriot President Nicos Anastasiades, the family of Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta, and the ruling family of Azerbaijan, among others.

• One of the revelations is that a woman rumored to be in a secret, long-term relationship with Vladimir Putin owns a multi-million dollar apartment in Monte Carlo.

• Jordan’s King Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein secretly spent more than $100m on a property empire in the U.K. and U.S., and the family of Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta secretly owned a network of offshore companies for decades, according to the Pandora Papers.

• Allies of Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelenskiy sought to justify his use of offshore companies, arguing they protected him against corrupt pro-Russian politicians, Al Jazeera reports.

• The Czech national police announced they would investigate any Czech national named in the Pandora Papers, including the current billionaire Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, who is up for reelection, the Washington Post reports.

• In more bad news for Babiš, his ANO party was edged out by the two opposition coalitions trying to unseat him, meaning that he will almost certainly lose the premiership, CNN reports.

• South Dakota is the new hotspot where the global elite is hiding its stolen money, per the Washington Post.

• NATO expelled eight members of Russia's mission for spying, the Guardian reports.

• Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz announced he is stepping down after being placed under investigation on suspicion of corruption offences, Reuters reports. But he plans to stay on as the leader of his party and its top lawmaker in parliament.

• The Australian government announced that it will stop processing asylum-seekers at detention centers in Papua New Guinea and will send all asylum-seekers to Nauru instead, the New York Times reports.

• An International coalition including the U.S., France, Ukraine, and the European Union coordinated the arrest of two hackers involved in ransomware attacks. The arrests took place in Ukraine, the Hill reports.

• Quite the list of bylines on this Politico Europe op-ed: Catherine Ashton, Misha Glenny, Mark Medish, Alexander Rondos, and Ivan Vejvoda write that the European Union shouldn't close the door on the Western Balkans.

• Reports by Der Spiegel, Libération, and other European outlets revealed that authorities in Croatia, Greece, and Romania engage in the illegal pushback of migrants arriving at their borders.

• Poland’s constitutional tribunal ruled that some E.U. laws are in conflict with Poland’s constitution, the Guardian reports. Politico Europe reports that the ruling puts Poland on a collision course with the EU’s legal order.

• A judge in Italy delayed Spain’s request to extradite former Catalan separatist leader Carles Puigdemont, Politico Europe reports. The judge is awaiting a decision by a European court on whether Puidgemont has immunity from prosecution.

• Georgia's ruling party, Georgian Dream, won local elections by garnering around 46.7% of the votes, Reuters reports. A mission of observers from the OSCE said the election was "marred by wide-spread and consistent allegations of intimidation, vote-buying, pressure on candidates and voters, and an unlevel playing field."

• A former member of China's security service exposed the torture methods Chinese officials used in Xinjiang province to force Uyghurs and other minorities to confess to alleged crimes. The detective said every new detainee is beaten during the interrogation process — including women and children, CNN reports.

• In anticipation of further aggression from China, Taiwan is preparing for war and asked Australia to increase intelligence sharing and security cooperation, according to Taiwanese Foreign Minister Joseph Wu, ABC Australia reports.

• The Wall Street Journal reports that the U.S. secretly maintained about two dozen special-operations soldiers and an unknown number of marines in Taiwan to train Taiwanese forces for at least the last year.

• The Wall Street Journal also reports that CIA Director William Burns is establishing a major organization within the CIA focused on China.

• The Wall Street Journal reports that Kabul could face an electricity blackout because the Taliban hasn't paid Central Asian electricity suppliers or resumed collecting money from consumers.

• The United Nations says Libya is carrying out an unprecedented crackdown on migrants, with over 5,000 people being rounded up, including hundreds of women and children, the Associated Press reports.

• The U.N. Human Rights Council found that war crimes and crimes against humanity – including murder, torture, enslavement, extrajudicial killings, and rape – have been committed in Libya since 2016. The Council said there were “reasonable grounds to believe” that Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group committed murders and that the European Union-trained Libyan coastguard handed migrants over to detention centers where torture and sexual violence were “prevalent," the Guardian reports.

• The Ethiopian government used state-owned Ethiopian Airlines, the country’s flagship commercial airline, to smuggle weapons to and from Eritrea during the civil war in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, according to a CNN investigation.

• Qemant refugees in disputed territories of the Amhara region of Ethiopia, south of Tigray, have accused the Ethiopian military and civilian mobs of ethnic cleansing, Al Jazeera reports.

• Iran asked the U.S. to unfreeze $10 billion of its funds as a condition for resuming nuclear deal talks, Reuters reports.

• Saudi Arabia’s government publicly confirmed that it has been holding talks with Iran to reduce tensions between the two countries.

• Syria’s President Bashar Assad called Jordan’s King Abdullah II in the first conversation between the two leaders since Syria’s civil war began, the Associated Press reports.

Upgrade to a premium subscription by Clicking Here.

As always, you can contact me with questions, complaints, corrections, or for any reason at all: c.maza@protonmail.com. And if you like this newsletter, please share it on social media or with a friend.